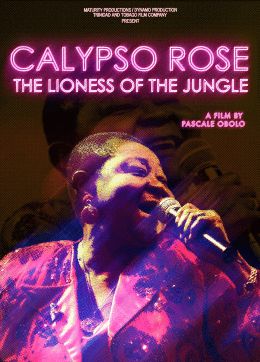

Dancers at the Notting Hill carnival, 2009. Photograph: Nicholas Bailey/Rex Features

‘Look at them,” instructs Clary Salandy, her voice growing ever more urgent. “Those boys are making hats. Those girls are making costumes. Those over there are welding structures for the costumes. They are creating things. They are not rioting. They like Nike and all that stuff but they are here working until the early hours and then they go to the shop and buy them. We have seen what some kids do. Carnival will show what our good kids do.”

It will if Clary has anything to do with it. She’s a veteran, colonel-in-chief of the celebrated “masquerade” band Mahogany. Its vivid designs and brightly coloured processions have been a highlight of every Notting Hill carnival that anyone can remember. That’s no accident. Mahogany know what they are doing and they worry about the details. An instruction here, some encouragement there; from her shop premises on Harlesden High Street in north-west London, Clary runs a tight ship.

It is people like Clary who put the spectacle on the street and make carnival happen. It’s hard work, not least because the event carries expectations commensurate with being the biggest street festival in Europe. But this year the stakes could not be higher.

The 46th Notting Hill carnival will attract a million people this weekend – more if the sun shines – and, as always, placing that many revellers in such a small space presents particular challenges. But it will also be the first big public event in London since the terrible riots that scarred the capital and other cities just three weeks ago. The first chance for the mob to run amok again, if permitted – and so inclined. For many reasons, that cannot be allowed to happen.

One is the future of carnival itself, for the event is popular but never universally so. Another is the reputation of the Metropolitan police, which met such criticism, not least from the prime minister, for the tactics deployed when the rioting spread from Tottenham and the looters appeared to have the upper hand. Another is the reputation of London, with the Olympics barely a year away. Then there is the reputation of the UK itself. No one cares to contemplate more shamefully embarrassing images of disorder making their way around the world.

So no chances are being taken. There will be a record 16,000 police officers on duty. Preliminary raids have already been carried out to identify known troublemakers and ban them from carnival. The event itself will provide between 500 and 700 stewards. This year, in an unprecedented move, everything will wind down at 7pm.

Notting Hill carnival, 1975. Photograph: John Hannah/Rex Features

One senior officer tells me carnival is being seen as a litmus test. “There is definitely a keen perception of the risks involved,” he says. “Not just at carnival but also the risk from those elements who think they might be able to fill their boots in other areas while so many officers are at carnival. We got a bloody nose in Tottenham and in other areas and we can’t afford to have this at carnival. The last thing we need is more pictures that say London isn’t safe.”

So the runup is a nervy one. But then, has there ever been a year when malign forces have not been conspiring to derail the Notting Hill carnival? No one can remember one. Consider the money. It is expensive to stage, the direct organising costs alone being around £500,000. Add in the amounts spent by the police and other public services, particularly the council cleaners, and then consider that for much of its life there has been no easy assumption that politicians or donors or individuals or corporations would come forward in sufficient number to fund it.

Consider that, even now, the event has no primary commercial sponsor and that much of the most vital work involved in putting the show together is done by volunteers.

In recent years it has been relatively tranquil, with new faces at the top and a marked improvement in the management of the event, but money has long been a problem. In 2003 the Arts Council refused to give the organisers a proposed grant of £160,000 because of perceived irregularities in the accounting. The Greater London Authority in response decided to steer its grant for stewarding away from the organisers and to pay the companies concerned directly. Three years ago, the new team took over and discovered that the event was seriously in debt.

Consider crime. Even without the backdrop to this year’s event, carnival has been forced each year to answer those who say that in terms of crime and antisocial behaviour, the annual revelry is a price not worth paying. Last year’s event was relatively peaceful. But these things, critics say, are indeed relative. Crime was down by 31% compared with the previous year, and some crime is inevitable, but still there were, at one stage, bottles and missiles thrown at police and 280 arrests.

Consider the route, always a point of contention, which one might expect given that last year up to one million people crammed the narrow streets of Notting Hill. Thousands flock to west London. At the same time, scores of residents keen to avoid the noise and disruption move out.

“Notting Hill carnival is almost here,” said one press release sent out on Wednesday, a catalyst, “for those toying with the idea of getting away over the August bank holiday.”

Jennette Arnold, the chair of the London Assembly and a member of the Metropolitan Police Authority, believes carnival has only intermittently enjoyed the sort of support it deserves. “There has been an ambivalence about it. I think it is the jewel in the crown of London’s cultural life. But many throughout its history have seen it as just a black event. They have viewed it negatively, seeing only the potential for trouble.”

A reveller confronts a policeman at the 1976 Notting Hill carnival. Photograph: Homer Sykes

The event has regularly faced the threat of being taken off the streets, particularly those gentrified Notting Hill streets familiar to residents such as David Cameron and Michael Gove, and being cocooned in a more manageable open space, such as Hyde Park. Had the Royal Parks been more amenable to the idea, few doubt that by now it would have been condemned to such a fate. And to those who see carnival as just another festival – a black lord mayor’s show with dancers and tinsel – that approach might seem to make sense. But there is a history and a philosophy to carnival that sustains it, and frustratingly for politicians who would like to get a better handle on it, makes the event hyper-sensitive and hyper-resistant to change.

Claudia Jones, the veteran Trinidadian communist, activist and publisher exiled as a menace from America, is always known as the Mother of Carnival. The first one organised by her in 1959 was largely static, in St Pancras town hall, and was designed as both a comfort and a statement. The race riots in Notting Hill had scarred the area and shocked the nation the year before.

The first carnival as we know it in Notting Hill itself took place in 1964 when, spurred on by another pioneer, Rhaune Laslett, marchers and steel bands spilled on to the streets with their artistry. That took chutzpah, for though many embraced the idea and welcomed a dash of colour to what was then a down-at-heel district, race relations in Notting Hill were a constant difficulty. In his new re-investigation of the 1959 murder in the heart of Notting Hill of a black man, Kelso Cochrane, author Mark Olden brilliantly describes a postwar world where feral young white men, drunk on beer, high on bravado, terrified at the emergence of a community they did not recognise or understand, made a statement of their own with regular bouts of “nigger hunting”.

So carnival was a pointed response to recent domestic events. But it was more than that. Trace them back – the dances, the rituals – and they transport one back to the West Indies, but don’t stop there. They transport those who know back to the emancipation of forefathers from hundreds of years of slavery. The whole thing, beneath the swaying and the jollity, could not be more historically loaded.

Professor Gus John, the historian, author and government adviser says: “People must understand the origins of carnival. It is a festival created by freed slaves in the Caribbean in a period when the only opportunity they had to express themselves and their culture was at the end of the sugar cane crop. The British and French had banned the use of drums, cow horns and conch shells; not only because they were used in traditional religious practices that they wished to outlaw, but because they were also used to organise rebellions. In time, the resourceful workers started making percussion instruments with sticks and with bamboo and with metal implements.” Forerunners of the steel drums. Part of the ritual, he says, was a joyful mocking. “Carnival has always been associated with self-affirmation, assertion of cultural identity and African origins and a parodying of the habits, dress, mores and lifestyle of the oppressor class. The festival has always combined music, drama, costumery and satire.”

What happens, Clary tells me, while quality-checking a pointed yellow hat beautifully crafted from gold plastic and white foam, happens for a reason. “It is on the street and it stays on the street because once there were laws forbidding black people to be on the street. No more than 10 were allowed to congregate. We are not taking it to a park behind a fence. No way.”

There is a bitter irony this year, he adds. Unsolicited, it falls to carnival to provide some joy to erase the rancour, to show off London’s diversity, to rehabilitate the nation’s reputation as a place where mass events can occur without near anarchy. And yet recently, when there was a chance to truly embrace and promote carnival as part of the Cultural Olympiad for the 2012 Olympics with a widely trailed Festival of Carnivals, the officials responsible decided at the 11th hour not to bother. “One minute the money and the will was there,” Clary says. “We were all preparing to be part of it. The next it wasn’t. When I think of all the good that could have been done with that money, all the young people we could have engaged, doing things, learning things, it makes me disillusioned. What we do is world class. But we don’t get the respect.”

There is something unsatisfactory about the establishment’s relationship with carnival. It is liked – a study for the GLA in 2004 suggested it pumps £93m into the London economy. But it isn’t loved in the way that Rio loves its yearly spectacle. It too suffers from crime, sometimes deaths, but these never lead to a questioning of the fundamentals. It is one of the key ways in which the Brazilian city sells itself to the world. For all its longevity, carnival has never enjoyed that status here.

As a director of the Notting Hill Carnival Trust for the past three years, it’s now Chris Boothman’s job to change that. It’s a mammoth task, but many feel that so far it’s going well. After two years of internal changes and the forging of new relationships with politicians and the commercial world, this was to be the year carnival showed a new, confident face to the world. The goal is still to make sure everything goes right this weekend. Most believe that will happen. But more than that, it can’t afford to get anything wrong. Pressure aplenty but Boothman, a solicitor, once the legal head of the now defunct Commission for Racial Equality, a member of the Metropolitan Police Authority and a veteran carnivalist, has the sang-froid of a man who’s coping. “There will be 4,000 extra police a day on duty in the carnival area but they won’t be in the immediate area of carnival,” he tells me. “The look and feel of carnival won’t be much different. But they will be available if needed.”

Carnival always weathers the storms, he says. “There are people who annually whip things up; a small and hardcore number of individuals who want it scrapped and talk about violence when in fact the event is getting safer every year.”

He loves the traditions, but is unafraid to modernise. “The street parade will never disappear but part of the challenge is getting back to the way it used to feel. It has got so big.” Thinking aloud he wonders if they might extend the six-mile route. Or extend the event itself into a season, like the Edinburgh festival.

He hopes and expects to be able to continue that work unimpeded, with the aspiration that next year’s event, in Olympic year, will attract both establishment love and sponsors, creating a new normal. “The 80s riots never impacted carnival. When there was trouble, it was about issues between black youths and the police. But people rioting and looting is not something we expect to see at carnival. We have worked hard to get this far. Whatever happens, we’ll be here.”

For original article: The importance of the Notting Hill carnival | Culture | The Guardian.