The following feature was written by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro and published in the New York Times Magazine on Oct. 9, 2011.

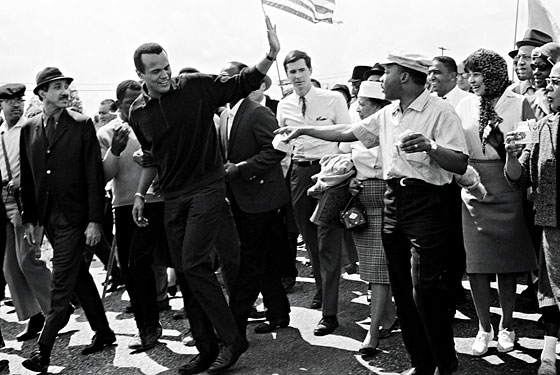

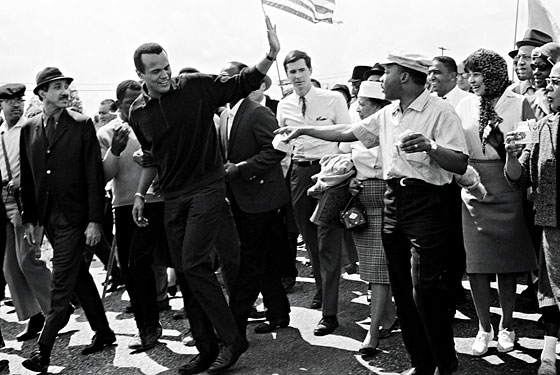

Belafonte waves to Martin Luther King Jr. (right) at a 1965 civil-rights march in Montgomery, Alabama. (Photo: Bettmann/Corbis)

In 1956, a Harlem-bred child of Caribbean immigrants released the first million-selling LP in history—Harry Belafonte was bigger than Elvis. But where Elvis built Graceland, Belafonte used the proceeds from Calypso to bankroll his friend Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement for civil rights. In an absorbing new memoir, My Song, as well as an HBO documentary, “Sing Your Song,” Belafonte recounts a life that took him from an impoverished childhood in Harlem and Jamaica to studying theater, as an angry young man in the postwar Village, with his close friend Marlon Brando; to finding pop success, in the fifties, as a smiling folksinger and America’s first black matinee idol; to becoming, in the years surrounding John Kennedy’s assassination and the March on Washington, perhaps the key go-between for King’s movement and the federal government. The only man to speak to both King and Bobby Kennedy on a daily basis through those years, Belafonte also persuaded JFK to approve airlifting a planeload of Kenyan students to America in 1961. That a certain Barack Obama Sr. was on that plane, one feels, isn’t the sole link to draw between his son and a figure whom the future president’s mother grew up adoring as “the handsomest man in the world,” according to one account. West Indian–American, angry charmer, elder radical, critic of a president who would not have been possible without him—Belafonte is a man of many conflicting identities, all of which he’s needed to help change the world.

You were born in Harlem, but your mother who raised you was a Jamaican immigrant. How do you think your Caribbean roots shaped your experience growing up?

Harry Belafonte: People from the Caribbean did not respond to America’s oppressions in the same way that black Americans did. We were constantly in a state of rebellion, constantly in a state of thinking way above that which we were given. My people were gangsters and lived in the underworld. And I don’t mean major American crime; I mean, as an immigrant, if you can’t find work inside the law, you find work outside the law. Running numbers and so on. Which is, of course, a characteristic of the poor, who find ways to break the rules, since the rules are always stacked against them.

You moved back and forth often between Jamaica and Harlem, sailing on the banana boats your father worked on as a cook. How do you think that movement, going between New York and the islands, shaped your understanding of race?

I had no particular crisis with white people. Because I never really saw them as in any way superior. Americans—black Americans—had crises, because not only were they forced to believe that white people were superior, but in many instances they bought it. And they made peace with it; we didn’t.

When you began singing folk songs in the early fifties, you were really coming out of the theater.

That’s right. I had come out of the dramatic theater, where the great writers of the day—Clifford Odets, Sean O’Casey—were concerned with politics, with working people. And those were the concerns I heard in Lead Belly, Seeger, when I was first hearing that music. Being involved in a lot of campaigns, helping people unionize, at rallies, helping them organize, picking up a picket sign, and walking in a picket line. And you sang songs on the picket line. So my engagement with the politics of music, and music as a political force, and using it specifically for that, came very early.

When you hit with Calypso in 1956, you gained fame very quickly. But just as quickly you sought to use that platform for other ends: in your work with Martin Luther King and then in your friendship with Jack and Bobby Kennedy, Bobby especially. In the beginning, though, you and Martin were quite suspicious of them; Bobby had been an ally of McCarthy, the blacklist.

We knew [before the 1960 election] that we must deal with reality. Somewhere down the line, we knew, we’re going to have to make the federal government yield to us. And I suspect that somewhere in this young man lies … good. So let’s put aside all his transgressions—the House Un-American Activities Committee, etc.—our task is to find his moral center and win him to our cause. Up until the day he died, we had a strong bond. But it wasn’t that way in the beginning. We circled one another for a long time; we kept a distance, even if we found reasons to use one another.

I know you’ve been spending a lot of time recently in your old neighborhood, Harlem. What strikes you about how the neighborhood has changed since your own, shall we say, delinquent youth there? How has the community changed?

One of the foremost things that we suffer from, for children, is the lack of models, of tangible role models. A lot of us, as kids, had no such problems. Because then, a lot of the achievers, they were also required to live in the middle of Harlem, or in the South Side of Chicago. “Rich nigs” couldn’t go anywhere. We saw Robeson. We saw Duke Ellington; he lived with us. Now none of those heroic figures live in Bed-Stuy or the heart of Harlem. Now they live in Martha’s Vineyard, Fire Island. In California, they live in Beverly Hills. So there is a definite segregation between role models. They’re not in our midst.

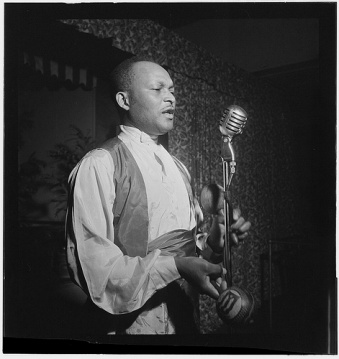

(Photo: Victoria Will/AP)

When you were close with the Kennedys, in those years when JFK asked you to help lead the Peace Corps, you persuaded him to sponsor African students to come to America, one of whom was our current president’s father.

We had the airlift, right. Myself, Jackie Robinson, Eleanor Roosevelt, and a woman called Cora Weiss. And we brought Kenyan students, before independence. To the chagrin of England. There was a huge foreign-policy glitch—England protested bitterly that the government permitted us to do this, without Kenyan visas. That we got them visas to enter American universities. And one of our lifts—and we didn’t have many—on one of those planes, we had Barack Obama’s father.

You praised Obama mightily when he was elected; you’ve now become highly critical of him. What do you think has happened to the president?

I don’t know that anything’s happened to Obama. I don’t know Obama. One can make assumptions, and you can glean things from what he says in his book, but it’s all pretty pat. I don’t know what Obama was intending to be, I don’t know what his game was. Being a community leader, being at Harvard … it’s all so squeaky clean. And I don’t know if he’s got a rabbit in the hat, that he’ll pull out at some point, startle all of us. But there has been no indication whatsoever that there is a rabbit in the hat. There’s been no indication that he even has a hat. So I treat him like I would treat anybody who sits in the seat of power. You push them as much as you can, awaken social consciousness, and try and go out there and make him do things.

My Song

By Harry Belafonte.

Knopf, $30.50.

Sing Your Song HBO.

October 17.

For original report: Harry Belafonte on His New Memoir, ‘My Song’ — New York Magazine.