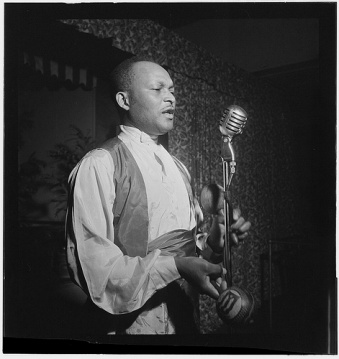

The following feature on Jamaican-born jazz legend, Andy Hamilton, was written by Steve Bradley and published in the Birmingham Mail.

“I GET quite angry – he should be given the freedom of the city.”

So says Birmingham historian Prof Carl Chinn about jazz saxophonist Andy Hamilton – still going strong at 94.

Hamilton, who arrived in Britain in the first wave of West Indian immigrants in 1949, came with a real pedigree as musical director on Hollywood legend Errol Flynn’s yacht Zaca.

But he has experienced some crushing ‘downs’ sprinkled with a few significant career ‘ups’.

Despite earning an MBE in 2008 for services to music and young people in Birmingham, he has endured racism, sometimes accompanied with violence, and had to battle to win regular gigs for himself and his band The Blue Notes.

Born in 1918 in Port Maria, Jamaica, Hamilton heard early US radio broadcasts and was exposed to the music of the Jazz Age in the 1920s.

Displaying a rare talent, he came to the attention of heartthrob Flynn, who owned the Titchfield Hotel in Jamaica’s Port Antonio.

“I think it was 1946 and I was playing there with my band on the terrace,” Hamilton recalled.

“Flynn had just come back from Hollywood and danced real close with his wife for a couple of numbers.

“The next morning a car and chauffeur arrived outside my house and the man said ‘Robin Hood wants to see you’.

“We went down to the harbour where he was on Zaca. Flynn said he liked my music and offered me a regular spot at his hotel.

“The Titchfield was the best hotel in Port Antonio so it was a good day for me and my band.

“He sure liked a good time. He had bought a small island called Navy Island and he used to have big parties there.

“One time he invited the whole crew of an American Navy cruiser, my band would play by the beach and there was a lot of dancing and people having a good time.

“People like Noel Coward and Ian Fleming lived close by and there would be lots of late-night parties.

“Flynn was a real good dancer and dressed real sharp. We became good friends and he kept saying I should go back and play in America but I came to England instead.”

Docking at Southampton, Hamilton took a train to London, then travelled to Manchester, but in little over a week chose Birmingham.

Hamilton made his base at a house in Trafalgar Road, Moseley, owned by Prof Chinn’s aunt Violet and Jamaican uncle Johnny Brown. “It was real tough at times, some places would not let us in and sometimes there was trouble but most people were friendly.

“I remember going to a jazz club with my sax and got invited up on stage and did a couple of numbers which went down real well.

“I was really happy but when I went back the next week they just ignored me.

“I went home real sad and decided the best thing to do was organise my own band and find places to play.”

Gigs followed at venues like the Tower Ballroom, Rum Runner, Chaplins, Cedar Club, plus nightspots in Coventry and Wolverhampton.

But in the 1950s he was attacked by fascists at a gig he had organised, losing his front teeth.

Hamilton, who married a white woman, Mary, said: “I had started a night and it had got popular, then one night a group of young guys came in and you could see they were looking for trouble.

“In a break one of them walked onto the stage and picked up my sax.

“I went up to him, real cool, and asked him to give it back but he was drunk and punched me in the face.

“The police came, I was arrested and had to go to court.

“A policeman who knew me spoke up for me and the case was dismissed – I am not sure what happened to the guy but I never saw him again.”

After decades of performing, Hamilton’s big break came when an article by renowned jazz journalist Val Wilmer earned him a slot at the Soho Jazz Festival in London.

From there he won a record contract with the World Circuit label to make his first-ever recording, aged 72.

Hamilton called the 1991 album Silvershine, named after a long-forgotten tune he had written for Flynn, and it featured Simply Red’s Mick Hucknall and US tenor sax giant David Murray.

Work was easier to come by after that, at least for a while, with shows in St Lucia, at the South African Jazz Festival, and WOMAD festivals across Europe.

He has since won an honorary master of arts degree from Birmingham University and a Millennium Fellowship award for his work in community education, to which he recently added a fellowship of Birmingham Conservatoire.

But although he holds down regular gigs at Bearwood Corks Club and in the Symphony Hall bar, he had to battle for years to get a slot at the Birmingham Jazz Festival. And his band, which has featured two of his sons, Graeme and Mark on trumpet and saxophone respectively, is made to feel it still has something to prove.

Andy said: “There have been some tough times with a big family and with a six or seven-piece band to pay and equipment to buy.

“I have never really made any money from music, I am certainly not rich. It made me very proud to get an MBE from Prince Charles at Buckingham Palace but it doesn’t help pay any bills.”

For the original post: The amazing life of Brum jazzman Andy Hamilton, who played for Errol Flynn, Noel Coward and Ian Fleming and has just turned 94 – Top Stories – News – Birmingham Mail.

Also: Repeating Islands