The following is the announcement and obituary released by the Center for Black Music Research on the occasion of the death of the Center’s founder – Dr. Samuel Floyd Jr.

Dear CBMR friends and associates:

With great sadness, I write to inform you of the passing of the CBMR’s Founder and Director Emeritus, Dr. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., who died on Monday, July 11, in Chicago, following an extended illness.

Please see the attached obituary, which was written by former colleagues Suzanne Flandreau, Morris Phibbs, and Rosita M. Sands. It will also be posted on the CBMR web site, at http://www.colum.edu/cbmr. I know that all of us who knew Sam personally or had the opportunity to work with him professionally, profoundly mourn his loss. Yet we are grateful for the rich legacy of work he leaves behind that has forever changed the landscape of musicological research.

Sincerely,

Dr. Rosita M. Sands, Interim Director, CBMR; Chair, Music Department, Columbia College Chicago

Dr. Monica Hairston O’Connell, former Executive Director, CBMR

Morris Phibbs, former Deputy Director, CBMR

Suzanne Flandreau, former Archivist and Head Librarian, CBMR

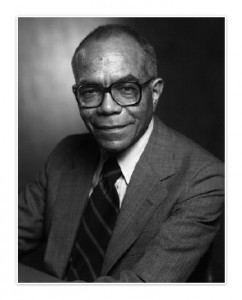

Dr. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr.

2/1/1937 – 7/11/2016

Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., educator, musician, scholar and champion of black music research died in Chicago on Monday, July 11, after an extended illness. Dr. Floyd was born in Tallahassee, Florida, on February 1, 1937. He received his bachelor’s degree from Florida A & M University and later earned a masters (1965) and Ph.D. (1969) from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. He began his music career as a high school band director in Florida before returning to Florida A & M to serve as Instructor and Assistant Band Director under legendary band director William “Pat” Foster. In 1964 he joined the faculty at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, and in 1978, he began a faculty position as Professor of Music at Fisk University, where he founded and served as Director of the Institute for Research in Black American Music. In 1983 he moved to Columbia College Chicago to found the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR), which became an internationally respected research center under his leadership. Critical to the creation of the CBMR was the establishment of the CBMR Library and Archives, which has grown to be one of the most comprehensive collections of music, recordings, and research materials devoted to black music. At Columbia College, Dr. Floyd also served as Academic Dean from 1990 to 1993 and as Interim Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost during 1999–2001. He retired as Director Emeritus of the CBMR in 2002.

At the CBMR Dr. Floyd devoted himself to discovering and publishing the information that would allow black music to receive its rightful recognition from audiences and scholars. His early publications (with Marsha Heizer) were bibliographies of research materials and biographical resources. Later he edited a collection of essays, Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance (1990), which won the Irving Lowens Award for Distinguished Scholarship in American Music from the Society for American Music. He also edited the International Dictionary of Black Composers (1999) a reference book that won several awards from the library community, including an honorable mention for the American Library Association’s Dartmouth Medal in 2000.

While still at Fisk, Dr. Floyd founded Black Music Research Journal, a juried scholarly journal which moved with him to the CBMR in 1983; it has been published continuously since its founding in 1980. He also founded and edited a grant-funded journal, Lenox Avenue: A Journal of Interartistic Inquiry, dedicated to exploring the role of music within the broader arts of the African Diaspora, the Music of the African Diaspora book series, which is published by the University of California Press, a monographs series, and several newsletters. Under his direction, the CBMR held numerous national and international conferences highlighting scholarly research, sponsored a series of postgraduate research fellowships funded by the Rockefeller Foundation for scholars studying the music of the African Diaspora, and taught two seminars for college teachers on African-American music, under the auspices of the National Endowment for the Humanities. He also established the Alton Augustus Adams Music Research Institute in St. Thomas (2000–2006), U.S. Virgin Islands, to study and document black music throughout the Caribbean.

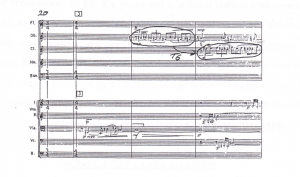

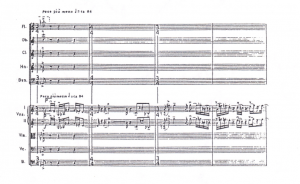

Performance was another important aspect of the CBMR’s programming. Dr. Floyd created four professional ensembles at the CBMR: the Black Music Repertory Ensemble, devoted to music by black composers; Ensemble Kalinda Chicago, which performed African-influenced music of Latin America and the Caribbean; Ensemble Stop-Time, which concentrated on African-American popular music and jazz; and the New Black Music Repertory Ensemble, which combined the performance capabilities and repertoires of the previous three ensembles. The ensembles, which introduced audiences at every level to black music, produced recordings, performed nearly 200 concerts locally and on national tour, recorded eight nationally broadcast radio shows, and presented lecture-demonstrations in schools.

Dr. Floyd was a prodigious grant-writer who won significant funding to help support the CBMR’s public programming and the development of the CBMR Library and Archives. Among the most supportive agencies were the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Illinois Arts Council, the Institute for Museum and Library Services, the Chicago Community Trust, and the Sara Lee, Joyce, Ford, John D. and Catherine T. Rockefeller, MacArthur, and Fry foundations, among many others.

Samuel Floyd was a true visionary. Through the CBMR he was able to realize his concept of black music as a totality expressing African Diasporic culture across genre and time. His book, The Power of Black Music, published by Oxford University Press in 1995, epitomized his ideas. It was one of the first scholarly studies to transcend historical reporting and synthesize the information he had founded the CBMR to discover and preserve. In his retirement he was engaged in further studies intended to carry his synthesis even further. Two new books are scheduled to be published by Oxford University Press.

Among the awards received by Dr. Floyd in recognition of his vision, service, and contributions are: the National Association of Negro Musician’s Award for Distinguished Contributions to Music, the Pacesetters Award in recognition of Outstanding Achievement in Higher Education from the American Association of Higher Education Black Caucus, and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society for American Music. Floyd was a Fellow at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities, and was twice a Fellow at the National Humanities Center, Research Triangle, North Carolina, including a term as the John Hope Franklin Senior Fellow. He was also Scholar-in-Residence at the Bellagio Student and Conference Center (Italy), a Robert M. Trotter Lecturer for The College Music Society, and was named an Honorary Member of the American Musicological Society.

Dr. Floyd is survived by his wife of over 50 years, Barbara, and their three children—Wanda, Samuel Floyd III, and Cecilia. No formal memorial has been planned by the family and services will be private. Expressions of condolence may be sent to Mrs. Barbara Floyd, 2960 North Lake Shore Drive #408, Chicago, IL 60657. In lieu of flowers, donations in his memory may be made to benefit his alma mater at the FAMU Foundation, 625 East Tennessee Street, Suite 100, Tallahassee, FL 32308-4933. http://www.famu.edu/index.cfm?GiveToFAMU&FoundationHome.