The following is the link to a pdf version of my essay on aspects of the compositional style of the late African-American composer, Ulysses Kay.

Tag: Ulysses Kay

This essay examines two of Kay’s compositions: his Scherzi Musicali (1968) written for chamber orchestra, and First Nocturne for piano, which was composed in 1973. In analyzing these two pieces I aim, firstly, to show that Kay progressed stylistically to be worthy of the classification “full-fledged modernist” and reveal some of the twentieth century Art Music compositional procedures that Kay utilized. In doing so I rely primarily on the tenets of post-tonal musical analysis as outlined in Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory[7].

SCHERZI MUSICALI

First Movement

Kay wrote this work in 1968 for chamber orchestra of flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon, and strings. The Chamber Music Society of Detroit commissioned it on the occasion of its Twenty-fifth Anniversary. Scherzi Musicali is atonal in its entirety and it shows that Kay had fully embraced twentieth-century techniques of composition. This piece is aggregate-based in which the composer ensures the circulation of all twelve tones of the chromatic scale throughout most of the work. It also presents and develops the all interval heptachord (0123456).

Form

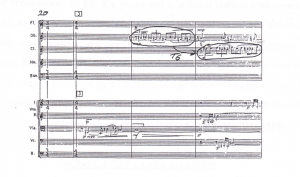

The first movement is AB in form with and introduction and coda. The introduction is distinguished by a static texture created by the superimposition of the notes of the heptachord [B, C, Eb, D, C#, E, F] on each other. This heptachord is transposed at rehearsal marking 1 (mm. 7), but the texture remains the same (see ex.1).

Ex.1 shows the title page of Scherzi Musicali.

Section A begins in measure 13 with the P designation in the flute. This section presents a linear, contrapuntal working out of thematic ideas and it is characterized by the triplet rhythmic pattern, which is featured in the upper woodwinds throughout. During measure 13-19, the flute carries the triplet pattern and it is taken up by the oboe and clarinet in measures 22-26. The triplets then return to the flute in measure 33.

In this section, each instrument is given its own melodic line but there are imitative passages as well. Imitation is heard in measure 13 where the cello is answered by the viola and double bass respectively, and in measure 22-23, where the clarinet answers the oboe. The melody that begins in the second violin is answered by the cello, first violin, and double bass in succession (see ex. 2). Section A ends with a brief return of the introductory texture in measures 38-40.

Ex.2 shows measures 21- 23.

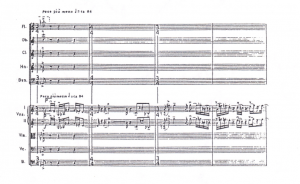

There is a change in tempo to poco piu mosso to mark the beginning of the B section. This section commences with the violins in unison, the only unison passage in this first movement. This passage, which spans measures 41-45, provides rhythmic contrast to the preceding triplets and possesses a proliferation of sixteenth notes (see ex. 3).

There is a change in tempo to poco piu mosso to mark the beginning of the B section. This section commences with the violins in unison, the only unison passage in this first movement. This passage, which spans measures 41-45, provides rhythmic contrast to the preceding triplets and possesses a proliferation of sixteenth notes (see ex. 3).

Ex.3 shows the first four measures of section B.

These sixteenth notes constitute the composite rhythm of the B section. After the strings, the oboe and then the clarinet carry this sixteenth-note figuration in measure 50-54. It is presented in a linear fashion until rehearsal 8 (mm. 55). At this juncture, the static texture of the opening returns and all the instruments of the chamber orchestra share the sixteenth-note figuration. At measure 61, the first violin takes up the figuration for one measure.

These sixteenth notes constitute the composite rhythm of the B section. After the strings, the oboe and then the clarinet carry this sixteenth-note figuration in measure 50-54. It is presented in a linear fashion until rehearsal 8 (mm. 55). At this juncture, the static texture of the opening returns and all the instruments of the chamber orchestra share the sixteenth-note figuration. At measure 61, the first violin takes up the figuration for one measure.

The coda is preceded by a measure of rest and marked by a return to the original tempo – tempo primo – in measure 68. It possesses the static texture of the introduction, which it imitates in “spelling out” set class (123456).

Click to view the entire essay

[7] Joseph N. Strauss. Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory, Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1990.

The Music of Ulysses Kay

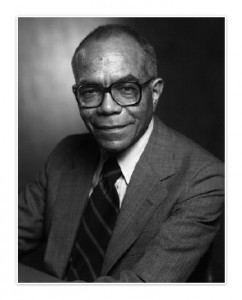

Today I commence the serialization of some aspects of my work on the music of African-American composer Ulysses Kay, which I have engage since 1995. In this post I present a brief biographical overview of Kay as a composer.

Today I commence the serialization of some aspects of my work on the music of African-American composer Ulysses Kay, which I have engage since 1995. In this post I present a brief biographical overview of Kay as a composer.

Click to view the entire essay

INTRODUCTION

The passing of African-American composer, teacher, and scholar Ulysses Kay, on May 20th 1995, marked the end of an illustrious career. Born on January 7th 1917, his musical education commenced at the tender age of six, when he began the study of the piano. Study of the violin was added in the ensuing years and he began to play the saxophone at age fourteen. It was around that tine that the young Kay became involved in a neighborhood combo and his interest in composition and orchestration was kindled.

In 1934 Kay entered the University of Arizona as a liberal arts major. He soon chose music as his major and graduated with his Bachelor of Music degree in 1938. He then pursued a Master’s degree in composition at the Eastman School of Music. Scholarship grants allowed him to study with the renowned German composer, Paul Hindemith, first at the Berkshire Music Center and then at Yale University.

Kay enlisted in the United State Navy in 1942 and played saxophone, flute, and piccolo in the Navy Band. He also played the piano in a dance orchestra. This period of military service (1942-46) proved to be extremely fruitful for Kay as a composer. Some of his compositions written during this period include: Flute Quintet (1943), Of New Horizons (1944), and Suite for Orchestra (1945), which received the B.M.I Orchestral award in 1947.

After the war, Kay studied at Columbia University on an Alice M. Ditson Fellowship. He was the recipient of numerous other fellowships: a Fulbright Scholarship, two Prix de Rome (scholarship awarded for study at the American Academy in Rome), a Julius Rosenwald fellowship, and grants from the National Institute of Arts and Letters. These allowed Kay to travel and study in Europe. During this period ne produced his Piano Quintet (1949), String Quartet No. 1 (1949), Brass Quintet (1950), Fugitive Songs (1950), and a film score: The Lion, The Griffin and the Kangaroo (1951), for a documentary filmed in Italy.

After returning from Europe, Kay became music consultant for Broadcast Music. He has been honored with prizes from the American Broadcasting Company and the New Jersey Council of the Arts. He has received commissions from symphony orchestras and universities, and has been the recipient of honorary degrees from Lincoln College (1963), Bucknell University (1966), the University of Arizona (1969), and Illinois Weslyan University (1969). In 1968, Kay was appointed Professor of Music at Lehman College, City University of New York, and became Distinguish Professor of Music at the university in 1972.

Kay’s offering to the twentieth century’s pool of music has been plentiful. As Hobson and Richardson point out, Kay produced mote that 135 compositions representing a tremendous outpouring of diverse forms[1] . His works include five operas, over twenty large orchestral pieces, fifteen chamber pieces, a ballet score, and numerous other compositions for voice, solo instruments, film, and television. Throughout his career, which spanned five decades, Kay’s music has received tremendous acclaim. Performances of his compositions have been reviewed in many literary publications, including the New York Times and the American Composers Bulletin. In fact, following his death, obituaries appeared in major print media such as: New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, and Amsterdam News. These obituaries all testify to the high regard with which Kay’s work had been held, and point to his significance as a twentieth-century composer.

Kay’s music has also been the subject of scholarly study. His choral works received the scholarly attention of Donald Armstrong, who in 1968 critiqued Kay’s compositions for women choruses, together with the works of other contemporary composers such as Elliot Carter, William Schumann, and Virgil Thomson[2] . And in 1972, Richard Hadley presented an analysis of Kay’s published choral music[3] . In his article Kay’s Fantasy Variations, Lucius Wyatt writes that the composer’s ingenious handling of the resources of the orchestra and his skillful organization of the harmonic, formal, rhythmic, and textural details, show Kay’s appreciation and understanding of the past, although he employs compositional techniques of the twentieth century[4] .

L. M. Hayes recognizes three stages in the development of Kay’s musical style. He points out that in the 1940s Kay produced music that contains a strong harmonic base with mild dissonances. In the 1950s his work becomes more contrapuntal, harmonies are more dissonant but tonality remains secure, although clouded by more active chromaticism. At the beginning of the 1960s, according to Hayes, Kay’s musical style crystallizes into a music that is articulate, expressive, moderately dissonant, lyrical, and predominantly contrapuntal [5].

Hayes goes on the note that Kay’s musical style has been termed neoclassical on occasion, and neo-chromatic at other times. He attributes this inability to firmly categorize Kay’s style to the fact that the composer successfully assimilated the styles and forms of past eras. Hayes concludes that the most accurate classification of Kay’s musical style should be that of eclectic modernist, since his music has a personality of conservative yet modern [6].

[1] See Hobson, Constance Tibbs, and Deborra A. Richardson. Ulysses Kay: A Bio-bibliography, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1994, 3.

[2] Donald J. Armstrong. A Study of Some Important 20th Century Secular compositions for Women Choruses, with a Preliminary Discussion of Secular Choral Music from a Historical and Philosophical Viewpoint, D. M. A. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 1968.

[3] Richard Hadley. The Published Choral Music of Ulysses Kay, Ph. D. dissertation, University of Iowa, 1972.

[4] See Wyatt, Lucius. “Ulysses Kay’s Fantasy Variations: An Analysis”. Black Perspective in Music 1 (1977): 75.

[5] See Hayes, Laurence M. The Music of Ulysses Kay, 1939-63, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1971, 332-334.

[6] See Hayes, 337-40.