The following report appears in Repeating Islands, Jan. 2, 2013.

Many thanks to Peter Jordens for the translation from the original “Owru yari wasi geen Marrontraditie” by Audry Wajwakana (De Ware Tijd). This post explains some of Suriname’s year-end and New Year’s traditions. Jordens provides clarification for key points.

On the last day of the calendar year, people in Suriname will put all worries aside and look forward to the new year with confidence. In keeping with (Afro-)Surinamese tradition, on this day hundreds of people go to Elly Purperhart on Independence Square for their annual swit watra wasi [sweet water cleanse].

[Swit watra consists of water to which aromatic liquids, herbs and flowers have been added. People either receive the swit watra from a gourd to wash their hands, arms, neck and face on the spot or take a bottle home for washing or bathing. In this way they enter the new year in a clean(sed) manner.]

Anthropologist Solomon Emanuels from the Santigron Maroon village says that this tradition diverges from Maroon culture, in which the ritual cleanse is not performed on New Year’s Eve. “Such rituals are performed one week before Christmas. This enables the individuals or families who live in discord with one another to settle their disputes before the holidays,” Emanuels explains. These rituals are also a way of bidding the old year farewell. “But because of integration into Surinamese society, you will get Maroons who do a wasi on Independence Square. There is nothing wrong with that, but it is not the tradition among Maroons.” There are specific Maroon rituals to welcome the new year. In the first week of the new year, a family member makes a libation to the gods and the ancestors in their Gaado oso [place of sacrifice]. This is accompanied by singing and people also bring rum and pangi [traditional cloth used as a wrap].

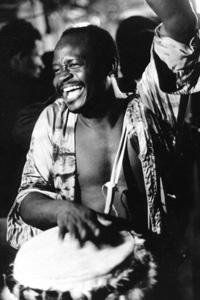

An important part of denyung yari [New Year] among the Maroons is the kromanti dance. Kromanti is the god of nature who consists of the elements water, fire and air. The dance is performed in the kromanti oso [place of worship], with much dancing and singing. “Some people may enter into a trance, allowing their body to be taken over by Kromanti who reveals whether they behaved well of badly last year and who instructs them to improve their habits in the new year. During this ritual predictions may also be made.”

According to Emanuels, more rituals used to be performed around New Year’s, but because of the changing times and integration into Suriname’s multi-cultural society, these have been lost. “Some Maroon communities do not even maintain their Gaado oso.” Emanuels says that this is an indication that society is changing and that the importance of religion is declining.

For the original article (in Dutch), see http://www.dwtonline.com/de-ware-tijd/2012/12/31/owru-yari-wasi-geen-marrontraditie

See also: New Year’s Traditions in Suriname « Repeating Islands.