In the following New York Times article, Margalit Fox reports on the passing of renowned Haitian dancer and choregrapher, Jean-Léon Destiné.

Jean-Léon Destiné, a Haitian dancer and choreographer who brought his country’s traditional music and dance to concert stages around the world, died on Jan. 22 at his home in Manhattan. He was 94.

Considered the father of Haitian professional dance, Mr. Destiné first came to international attention in the 1940s and remained prominent for decades afterward.

As a dancer, he performed well into old age. In 2003, reviewing a program at Symphony Space in New York in which he appeared, Anna Kisselgoff wrote in The New York Times that Mr. Destiné’s number stopped the show. She added, “He looked agile and nuanced, mesmerizing in a bent-legged solo.”

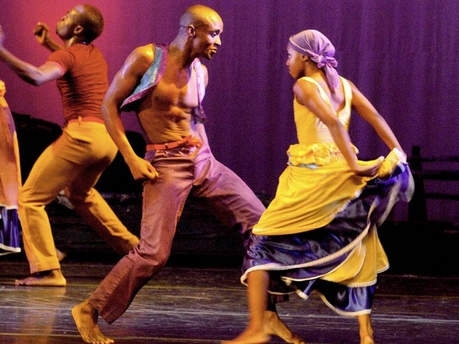

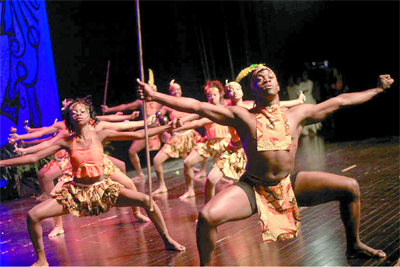

As a choreographer, he directed own ensemble, which came to be known as the Destiné Afro-Haitian Dance Company.

The company, which presented work from throughout the Caribbean, was devoted in particular to dances from Haiti. Accompanied by vibrant drumming — Mr. Destiné collaborated for many years with the distinguished Haitian drummer Alphonse Cimber — these dances were often infused with elements of voodoo tradition.

As reviewers noted, Mr. Destiné and company could dance, to all appearances, as if possessed.

Much of Mr. Destiné’s work also functioned as commentary on Haiti’s legacy of colonialism and slavery. In “Slave Dance,” a solo piece he choreographed and performed, the dancer begins in bondage only to emerge, in astonished joy, a free man.

In “Bal Champêtre” (“Country Ball”), among the most famous works choreographed by Mr. Destiné, the foppish customs of Haiti’s French colonists are satirized through sly subervsions of a Baroque minuet.

In the United States, Mr. Destiné was seen on Broadway; at the New York City Opera, where in 1949 he was a featured dancer in the world premiere of William Grant Still’s “Troubled Island,” set in Haiti; and, as a performer and teacher, with the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Becket, Mass. He also taught at New York University and elsewhere.

Jean-Léon Destiné was born on March 26, 1918, in Saint-Marc, Haiti, to a middle-class family: his father was a local government official, his mother a seamstress. After his parents divorced when he was a boy, he moved with his mother to the capital, Port-au-Prince, where they lived in reduced circumstances.

From a very early age, Jean-Léon was captivated by Haitian music and drumming. As a youth, he learned traditional dance by attending the religious rituals and other celebrations of which it had long been an integral part. He also sang in the folkloric ensemble directed by Lina Mathon Blanchet, a prominent Haitian musician.

In the 1940s, the young Mr. Destiné received a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship to study printing and journalism in the United States. After taking classes at Howard University in Washington, he moved to New York, where he learned to operate and maintain linotype machines, then used to cast type for printing newspapers other publications.

Mr. Destiné, who eventually became an American citizen, also continued dancing. In the late ’40s he spent several years with the company of Katherine Dunham, considered the matriarch of black dance in the United States.

With Ms. Dunham’s company, he danced on Broadway in the revue “Bal Negre” at the Belasco Theater in 1946.

Returning to Haiti for a time in the late ’40s, Mr. Destiné founded a national dance company there at the behest of the Haitian government. By the early ’50s he had established his own company in New York.

Mr. Destiné’s survivors include three sons, Gérard, Ernest and Carlo, as well as grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

For the original article: Jean-Léon Destiné, Haitian Dancer and Choreographer, Dies at 94 – NYTimes.com.